Film Discussion 29: Vertigo (1958)

For past discussions, or to sign up for the next episode, visit benjaminbrandt.com/film-discussions

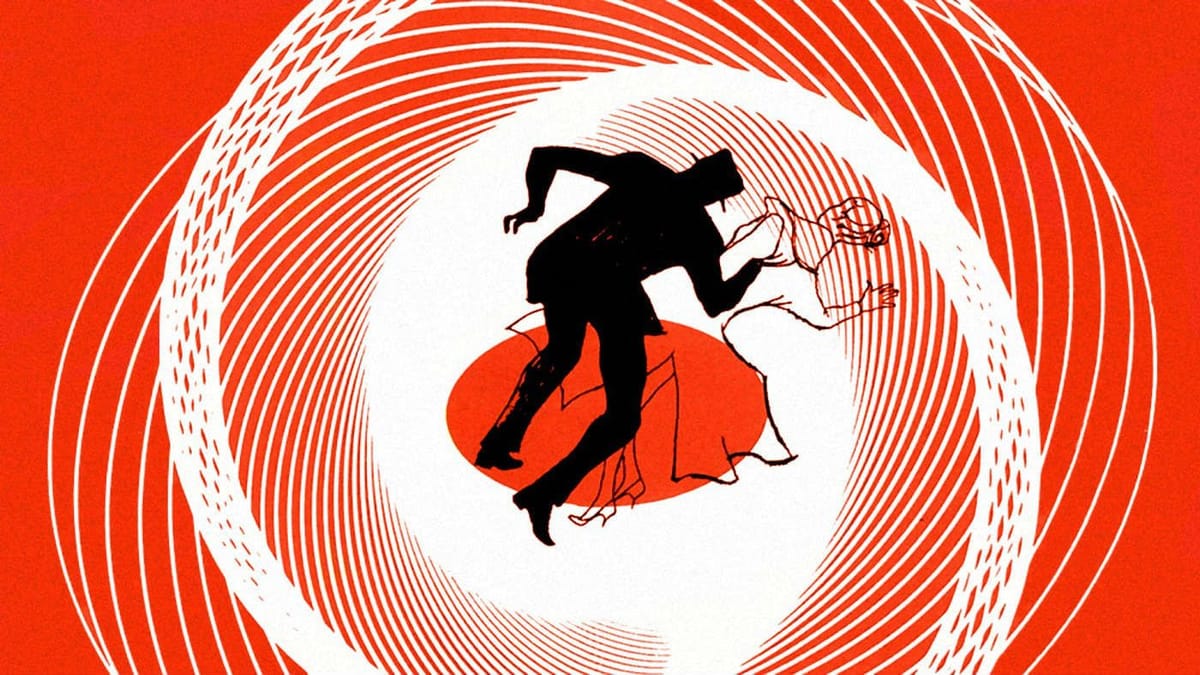

Josh and I held down the fort this month for a discussion of Vertigo. We continue to explore the relation of Hitchcock's films to our movie-going experience, the difference between love and desire, and our ability as humans to seek after an illusion rather than to truly face the reality in front of us.

Let us know what you think, and let me know if you want to join us for the next discussion!

Show Notes

C. Mason Wells on the film's relation to filmmaking

Hitchcock counted this as the most personal of his works, and it plays as a self-lacerating roman à clef, a deeply felt dramatization of the dark side of his filmmaking practice—the voyeuristic concerns of Rear Window (1954) pushed to their extreme. After Scottie loses his beloved Madeleine to suicide (or so it seems), he encounters her doppelganger Judy (Novak again), and proceeds to remake her in Madeleine’s image, all at once playing director, screenwriter, costume designer, even hair stylist. When Scottie learns the truth about Judy’s identity, this nightmarish Pygmalion scenario becomes a cautionary tale about the dangers of falling madly in love with a projection. What director can’t relate to that?

Carson Lund on the danger of substituting art for reality

When a nun suddenly enters the bell-tower of San Juan Baptista as a creeping shadow and sends Judy leaping out the window in the final moments of the film, to me she registers as Death arriving to put the inevitable end to Scottie's cycle of obsession and self-deception, not necessarily as a tangible catalyst to Judy's hysteria. In this way, Vertigo is brutally fatalistic about the punishing end result of obsessive objectification. It reveals Scottie's harrowing make-over of Judy back into Madeleine - a striving for a perfect vision of the past that was itself a facsimile - to be inherently flawed and destined for self-destruction. Like so many great works of art, the film is about the danger of substituting art for reality, the actual chaos and imprisonment (rather than bliss and perpetual satisfaction) that can result from too fervently seeking an ideal, an idea that the ever-meticulous Hitchcock implicates himself in.

Chris Marker on Scotty's fight against time and his lost 'love'

The vertigo the film deals with isn’t to do with space and falling; it is a clear, understandable and spectacular metaphor for yet another kind of vertigo, much more difficult to represent – the vertigo of time. Elster’s ‘perfect’ crime almost achieves the impossible: reinventing a time when men and women and San Francisco were different to what they are now. And its perfection, as with all perfection in Hitchcock, exists in duality. Scottie will absorb the folly of time with which Elster infuses him through Madeleine/Judy. But where Elster reduces the fantasy to mediocre manifestations (wealth, power, etc), Scottie transmutes it into its most utopian form: he overcomes the most irreparable damage caused by time and resurrects a love that is dead. The entire second part of the film, on the other side of the mirror, is nothing but a mad, maniacal attempt to deny time, to recreate through trivial yet necessary signs (like the signs of a liturgy: clothes, make-up, hair) the woman whose loss he has never been able to accept.